I recently came across this BBC article from Michael Mosley. In it, he explains the 10,000 step goal set by most fitness trackers is totally arbitrary, chosen by a Japanese marketing company in the 1960’s as part of the promotion of an early pedometer called the Manpo-Kei (literally, “ten thousand steps meter”).

This raises a simple question that should have a simple answer: If 10,000 steps is an arbitrary goal, how much physical activity should we get in a day?

The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services has this to say:

“adults should do at least 150 minutes (2 hours and 30 minutes) a week of moderate-intensity, or 75 minutes (1 hour and 15 minutes) a week of vigorous-intensity aerobic physical activity, or an equivalent combination of moderate- and vigorous- intensity aerobic activity.”

Getting specific

I have a lot of issues with the HHS guidelines. They’re not wrong, exactly, but they have a lot of problems, the biggest being that their recommendations use the vague and confusing terms moderate- and vigorous- intensity aerobic activity.

It’s particularly frustrating because we already have an industry standard for measuring absolute intensity of exercise: metabolic equivalent of task, or MET, which is a comparison of how much energy it takes to do a activity versus the energy it takes to sit quietly.

In other words, sitting is a 1 MET activity, and all other activities are then measured relative to that 1 MET baseline. Walking at ~3 mph takes three times the energy as sitting quietly, so it’s a 3 MET activity. Riding a bike at ~10 mph takes four times the energy of sitting quietly, so it’s 4 METs.

If you’re curious about the MET value of your preferred form of exercise, you can check out the Compendium of Physical Activities, which has standardized MET values for pretty much any physical activity you can think of, including ‘active, vigorous sexual activity12.8 MET’ and ‘spiritual dancing in church25.0 MET’.

Back to the HHS: to figure out what they mean when they say “moderate- and vigorous- intensity,” you have to dig around their website, find and download the full PDF report, and read 33 pages of semi-relevant information before you get to the definitions. On page 34 of the report, the HHS finally says:

“moderate-intensity activities expend 3.0 to 5.9 times the amount of energy expended at rest[, while] the energy expenditure of vigorous-intensity activities is 6.0 or more times the energy expended at rest.”

Sound familiar? THEY’RE USING METS! According to the HHS, moderate-intensity activity is 3-5.9 MET activity; vigorous-intensity activity is 6+ MET activity. (This, by the way, is when I get double frustrated: they’re already using METs, why not just use them in the recommendation? It’s already confusing for a layperson, might as well make it precise. ANYWAY.)

The guidelines, then, are recommending 150 minutes of aerobic activity per week at 3 METs and/or 75 minutes of activity at 6 METs. That can then be translated directly into the real recommendation of 450 MET-minutes per week, at any intensity higher than 3 MET. (MET-minutes are the MET value of an activity multiplied by the time you’re doing it, so 3 MET * 150 minutes = 450 MET-minutes; similarly 6 MET * 75 minutes = 450 MET-minutes.)

This also explains the confusing line at the end of the guidelines:

“[you can also do] an equivalent combination of moderate- and vigorous- intensity aerobic activity”.

They’re really saying that you can get to 450 MET-minutes of exercise any way you want, as long as the activities are at least 3 MET — so 150 minutes at 3 MET3walking at ~3MPH, 75 minutes at 6 MET4shoveling snow, 45 minutes at 10 MET5competitive racquetball, 30 minutes at 15 MET6running at a 6:30 pace, whatever. As long as the math works out to 450 MET-minutes total, you’re good by them.

So why 450 MET-minutes? Because at 450 MET-minutes per week, you’re already getting a majority of the health benefits of exercise, according to this 2012 study.7or a similar one; I couldn’t find the exact sources the HHS used

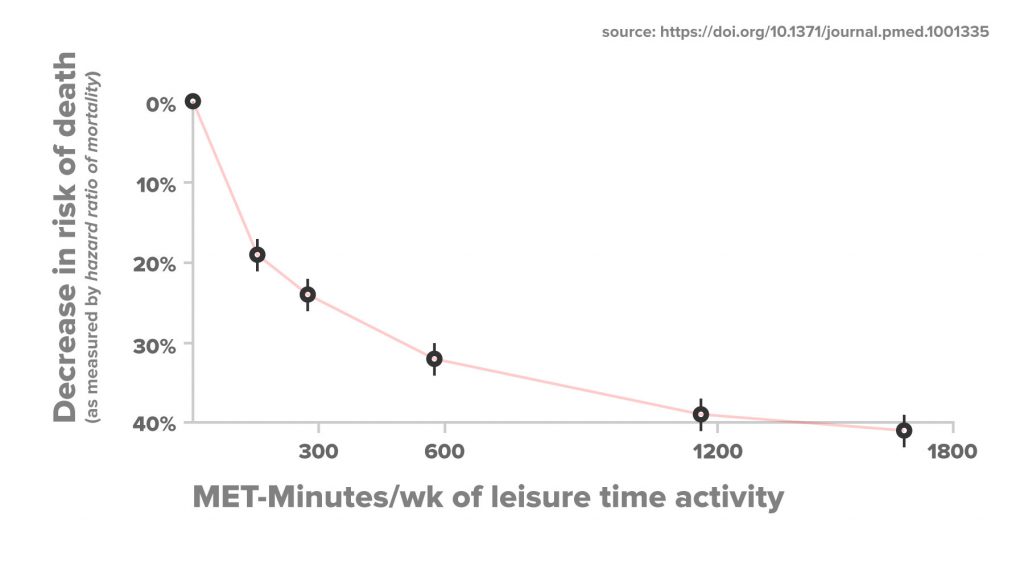

This chart from the above study explains it nicely: you can see that when you do 450 MET-minutes8The study (and the original chart) actually use MET-hours, but 7.5 MET-hours is the same thing as 450 MET-minutes; you just take 450 MET-minutes and divide it by 60 minutes per hour of exercise per week, your odds of dying decrease by 25%, but the total possible benefit is just a 40% reduction in mortality. You’re already getting more than half the possible benefit at 450 MET-minutes. Also, the slope of the curve becomes less than one after 450 MET-minutes, meaning that after 450 MET-minutes, you’ve hit the point of diminishing returns.

More is not always more

The extended version of the guidelines go on to say:

“For additional and more extensive health benefits, adults should increase their aerobic physical activity to 300 minutes (5 hours) a week of moderate intensity, or 150 minutes a week of vigorous intensity aerobic physical activity, or an equivalent combination of moderate- and vigorous-intensity activity. Additional health benefits are gained by engaging in physical activity beyond this amount.”

To translate, they’re saying that 450 MET-minutes is “enough,” but the “optimal” amount of exercise is anywhere between 900 and infinite MET-minutes of activity.

But that’s not strictly true: more is not always more when it comes to exercise. The research that the HHS uses for these numbers is measured all-cause mortality (read: odds of dying), not general health. It also lumps together any amount of exercise past 1350 MET-minutes per week as the same — but numerous other studies have shown that extreme amounts of exercise can actually harm your health.

This 2015 study of frequent joggers showed that joggers who ran more than 3x per week were actually more likely to die than joggers who ran 1-3 times per week, and that joggers who described their pace as ‘fast’ were also more likely to die than joggers who described their pace as ‘slow’ or ‘average’.

This brand-new study from the Mayo Clinic and this article in Nature are even more damning: very high levels of exercise can cause heart problems. People who got greater than 1350 MET-minutes of exercise per week were more likely to show signs of coronary artery disease than people who exercised right around the recommended 450 MET-minutes per week (although they were still less likely to show signs of coronary artery disease than people who didn’t exercise at all).

I’m not saying you shouldn’t exercise — far from it. You would have to be a highly dedicated, extreme athlete to cause serious harm to yourself via exercise. I’m just pointing out that this stuff isn’t as cut and dry as ‘more exercise is better’. As more and more research is done, it’s starting to seem like exercise actually has the classic u-shaped dose-response curve: more is better to a certain point, and then more actually becomes harmful.

So, how much should I actually exercise?

If you want to live as long as possible, period, with a decent quality of life throughout, you should probably do somewhere between 450 and 900 MET-minutes of low-impact 3–6 MET aerobic exercise per week in a safe environment. The classic example is briskly walking on a treadmill for 2.5 hours, or lightly jogging on it for 1.25.

You should probably also add in ~2 sessions per week of resistance training (which the HHS guidelines also recommend). While resistance training does increase your short term chances of injury, it also improves your bone density and motor control, leading to a better quality of life as you age and, ultimately, better odds of not dying.

In other words: follow the HHS guidelines. They’re not wrong. They’re worded in a way that is horrible for an average person to understand, and I have some other issues with their presentation and methodology (where are the sources?!) but they make sense once you break them down.

‘Don’t die quite as soon’ is a terrible motivator

But: walking and using weight machines to do the exact same low-impact thing a few times a week sounds boring to a lot of people (including me). Exercise shouldn’t be a chore that you have to do so you don’t die; exercise should be be fun — and not just because you’re (ideally) going to spend a decent amount of time doing it. Exercise should be fun, because if it’s boring, you’re not going to do it at all.

Any amount of exercise is better than no exercise, and the biggest mistake you can make is to think that if you can’t hit the HHS guidelines, it’s not worth it to do anything. Going from ‘no exercise’ to ‘any exercise’ group decreases your chance of dying by nearly 20%. If the only physical activity you can get is taking the stairs at work or getting your 10,000, so be it; it’s a hell of a lot better than doing nothing at all.

Similarly, excessive endurance exercise can be bad for your heart, but some people just love it. If that’s what you enjoy, don’t worry too much about the negative effects. Team sports have pretty high injury rates relative to other forms of exercise, too, but if pickup basketball is your jam, don’t let it stop you.

If you really are interested just interested in increasing life expectancy as much as possible in as little time as possible, you can also get away with just two 15 minute sessions of very-very-high-intensity (15 MET or more) interval training per week plus two resistance training sessions per week — in other words, two Crossfit classes. That kind of max effort training carries a much higher risk of injury and other negative effects, but who cares. It’s way better to do it than to do nothing at all.

Which brings us back to 10,000 steps. 10,000 is an arbitrary number, yes, and there are almost certainly better ways to work towards 450 MET-minutes, but 10,000 steps is simple, memorable, and measurable with a cheap pedometer.

Plus, if you’re like most people, getting to 10,000 steps normally means leaving the office at 4–6,000 steps and then needing to briskly walk for twenty to thirty minutes at some time in the evening (or over your lunch break, in the morning, etc) to make up the difference. Guess what? Not only is that literally the same thing that Michael Mosley from the BBC recommends, it also perfectly fits the HHS guidelines!

What do you like doing?

Ultimately, “How much exercise is enough exercise?” or its cousin, “How much should I exercise?”, aren’t the best questions to ask. A better question is: “What do I enjoy doing?”

Find a physical activity that you enjoy doing for reasons other than “if I do this, the day I die will be slightly farther in the future” and just start doing it. Then, look it up in the Compendium of Physical Activities, and find a way to start doing it enough that you’re hitting the HHS guidelines.

If you honestly can’t find the time to do it “enough,” then do it as often as you can. Remember: Anything is better than nothing.