Let’s talk about time blocking. I’m by far not the first to write about the concept1As far as I can tell, Cal Newport coined the phrase and wrote the first article about the idea, but there are dozens of pieces about it. Just google the phrase “time blocking” and you’ll find plenty (of varying quality)., but I want to cover it for two main reasons: I think it’s an extremely useful productivity tool, and I think it’s so much more than just a productivity tool.

Without (much) hyperbole, I think time blocking can be an effective tool for doing more of the things that we want to do, and ultimately for living a better, happier, fitter, more fun life.

We are all slaves to our calendars

The reason time blocking works so well starts with a simple, tragic fact: we are all slaves to our calendars. We are .ics addicts. “Send me an invite,” we say, “so I don’t forget.”

My entire professional and social life is managed by the blips and bings of my calendar app.2I’m intentionally not telling you which one I use because it doesn’t matter — time blocking will work with pretty much any calendar app.

Also, conversations about tools are way less interesting than conversations about about principles and strategies. Tools should be chosen after strategies are defined, not before, and finding “the perfect calendar app” is both a distraction from and proof that you suck at protecting your time and attention from yourself, because researching and choosing productivity tools and strategies is not the same as being productive. It’s just highly advanced procrastination.

Yes, I acknowledge the irony of saying this at the top of a 5,000 word article about productivity tools and strategies. My wrist, pocket, and laptop all remind me where I should be and what I should be doing at all points throughout the day, including after work and on the weekends. I create separate calendar events for every flight I take AND for the hourlong “pack, leave the house, and get there” window beforehand. I sent out a calendar invite for my birthday party.

I tried for a very long time to become less attached to my calendar, but it never took. I work with too many other humans, who all have different demands on their time. You probably do too. The calendar is a necessary tool for us to be able to work with others.

So, how do we make the best of this fact? Does being indentured to my calendar mean we can’t be in charge of our own time? If we can’t get rid of it, how do we make the best of it? Can we use the calendar to make life better instead of worse?

This is where time blocking comes in.

The value of time blocking

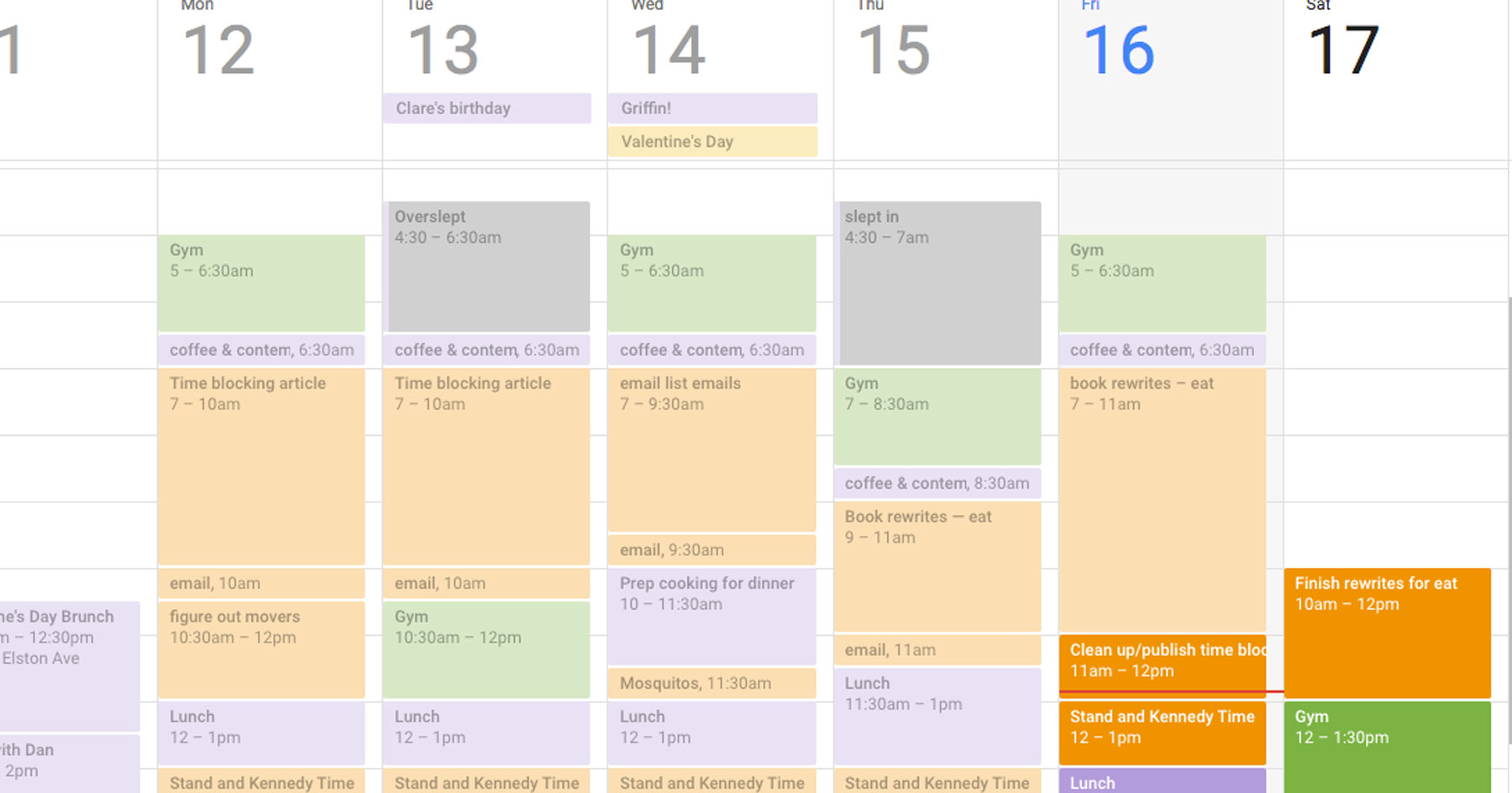

At its core, time blocking is just scheduling your to-do list against your calendar. You block off the time you’ll be working on a specific thing ahead of time, and then during that time, you work on the thing.

Say it’s Monday and you have a pitch or presentation that you need to draft by Thursday. You block off either a couple of hours on your calendar each afternoon between now and then, or — less recommended — an all-day marathon on Wednesday. That’s time blocking.

There are a lot of nuances to actually implementing a time blocking strategy — the pros and cons of blocking off your entire day, what things get blocked and what don’t, how far in advance to block, modifying your blocks on the fly and after the fact, etc — but time is the basic currency, and the action of “to-do list item => block of time on the calendar” is how you trade in it.

For such a simple concept, it’s a massively useful productivity tool, especially for consultants, technical leads, salespeople, product/project managers, analysts, and anyone else whose life falls somewhere in between the maker’s and manager’s schedule.

The reasons are many:

It makes you the master of your daily schedule.

Most people let their calendar completely dictate their time — if it’s on the calendar, it’s sacrosanct. But, they also only use it as a tool for other people take time from them.

This leads to late nights or early mornings catching up on “actual work,” because your time and attention was sapped away from you throughout the standard workday in the form of 30-minute meetings, hourlong calls, and other interruptions.3 nb: I don’t just mean getting stuck in back-to-back-to-back meetings all day, although that is a special kind of hell. Like Paul Graham says in the (above linked) Maker’s Schedule, Manager’s Schedule: “A single meeting can blow a whole afternoon, by breaking it into two pieces each too small to do anything hard in. Plus you have to remember to go to the meeting.” By blocking off your most important work time on your calendar before these distractions and requests come in, you can continue to let your calendar rule your time without giving up your most precious hours.

It is a socially-acceptable way to say no to time vampires.

Newport called the practice “time blocking” because the time is scheduled in large deep work friendly “blocks,” but it has a double meaning: it also blocks your time in the sense that it stops others from being able to eat into it.

“I’m booked solid until Friday, can we chat for five minutes now or do it over email?” is a much more tactful way to get out of useless, agenda-less meetings than “I’m trying to take fewer meetings right now. How important is this?” Put your calendar to “private” and the vampires don’t need to know that you’re the one that booked you solid; they’ll just see “busy.”

It balances the urgent with the important.

There are non-human time vampires, too: urgent but unimportant tasks also have the ability to fill a day and ruin your productivity if you’re not careful and intentional with your time.

With time blocking, you can still drop what you’re doing and handle a true crisis if it comes up, but planning what you’re going to work on ahead of time forces you to make a conscious choice to do so, rather than letting the urgent distractions automatically win.

It forces you to prove your priorities with action.

You want to write that article? Produce that big write-up of knowledge and lessons-learned from your last project? Research a new sales strategy? Get ahead on that big end of quarter presentation? Schedule it.

Just like a meeting, a time block is a commitment to show up and do a thing for a certain period of time. The only difference is that it’s a commitment to yourself; a commitment that something is important enough to you deserve time on your calendar.

It prevents procrastination.

To extend the above idea, scheduling time to work on things forces you to create the space to do them. If you’re rigorously time blocking and something still isn’t making the schedule, it’s probably not actually a priority (or there’s something else going on that’s stopping you from doing it).

It promotes deep work.

Solving hard problems takes a lot of time and attention. If you let distractions, multi-tasking, and other people take small drips of time from you all day, it’s hard to find more than a half-hour or hour at a stretch to do good, creative work — which is often barely long enough to get started. Forcing one task for one block of time allows depth; putting it on the schedule allows you to have the time at all.

It closes open loops.

This is a GTD idea; open loops are anything that needs to be done but doesn’t have a concrete next step. Open loops use mental processing power, draining your mental capacity in the same way having a bunch of apps open in the background on your computer drains its processing power. GTD works by capturing and defining the next step somewhere that is not your head, ready to act on at a later moment. This is helpful, but doesn’t answer the final open loop about any task: when will I do this? Time blocking answers this question.

It encourages batching.

You can’t (and shouldn’t) schedule blocks smaller than fifteen minute on most calendars, which means there’s no room in a time-blocked day for taking thirty seconds to check email or to do other tiny mosquitoes of tasks. Even if they don’t actually fill your time, these mosquito tasks distract you enough that never get into a productive state (see: deep work, open loops, maker/manager).

A much more productive and sanity-inducing way to handle these tasks is to batch them into one 15 minute block a few times a day, which time blocking naturally encourages.

Plus, by knowing that you’ve got 15 minutes after lunch blocked off to batch process all of your email, and/or 30 minutes at some point in the day labeled simply “mosquitos” — something I do — these little mosquito tasks don’t buzz around in your head taking up valuable mental energy. Just capture them on an index card or post-it, and work comfortably knowing that you already have the time to make them all happen at once later.

If you want to read more about batching, Tim Ferriss covers it extensively in The 4-Hour Workweek.

Your calendar keeps track of your day for you.

With time blocking, the calendar is no longer the interruption between your unbroken stretches of “actual work”; it’s the thing that reminds you what you’re actually working on and when to start (and end), which keeps you honest to your day’s plans and goals without having to constantly spend mental energy checking back in with them.

It forces you to be realistic with your time.

It’s really easy to put 10 things on your to-do list in the morning because you want to get those ten things done. It’s much harder to actually do them. By forcing yourself to at least guess how long each one will take while you take into account everything else you have going on (meetings, calls, hours in the day), it’s a lot harder to overcommit — there’s just no way you’re drafting that whole article before lunch if you have calls until 11:15.

It takes advantage of Parkinson’s Law.

Parkinson’s Law simply states “work expands so as to fill the time available for its completion.” Listing all of your to-dos as “things that have to happen today” lets your brain erroneously assume that you have all day to get all of them done. By knowing you “actually” only have 10AM to noon to get one specific task done, and that you’ve already blocked your afternoon out, you’re more likely to get it done earlier in the day and in less total time.

It creates a record of how you actually spend your time.

If you make a habit of updating your calendar as you finish your time blocks and even making notes about the task, you will naturally end up with an accurate week-over-week record of how your time is spent. This can be used in tricky ways—think easier billable hours and occasional CYA scenarios— or in more general reflective ways like realizing a third of your life is spent in status meetings, or that you only really get writing done if it’s done first thing in the morning before you talk to anyone else.

It trains you to be better at estimating how long things take.

When you reach the end of a task before the block is up or reach the end of a block and still have stuff to do, you know you guessed wrong. First, make a note to block off or rearrange time later in the week to finish the task. Then, take a second to ask yourself why you guessed wrong. Was there hidden complexity? An unknown dependency? Did you just let yourself get distracted? Make a mental or physical note for next time.

Time blocking as a life improvement tool

So far, I’ve been talking about time blocking as a system for maximizing your workday. This is the part where I talk about how its core principles can be used as a system for maximizing your life.

I discussed this a little bit in this article about becoming a morning person:

You already schedule your work hours, your flights, your meetings, important obligations and events, and probably a few other things. If it’s on the calendar, it happens. If it’s not, it doesn’t. If someone wants your time during those blocked-off moments, you either have to re-shuffle your priorities, or figure out another time.

Work should not be the only thing you treat this way. If you have things in your life that are as (or more) important to you than the things already on your calendar, put them there and defend them with the same discipline.

In fact, you should put them there first. Diligently time block everything non-work related before you time block your work, and watch as your work-life balance magically improves.

Keep getting held late at the office by last minute colleague needs? Or just by your own inability to stop thinking about work at the end of the day? Also have trouble getting to the gym? Set a recurring daily (or thrice weekly, or whatever) recurring event for gym time, and treat it just like you would an important call.

Tired of sitting on a call during lunch for the umpteenth time? This often happens because the lunch hour is the only overlapping free-looking time on most people’s calendars at short notice. Block off a recurring hour for lunch, and whomever is scheduling can either reach out to you personally for you to change it or find a more respectful time for everyone.

Want to do that professional development course, or start getting a certification, or work on a side business, but feel too swamped every week to schedule it in? Block time for it on your calendar three or four or however many weeks from now you need to see a free calendar, and when it comes up, don’t put it off. Keep it sacrosanct.

Are you like me and feel guilty about not working, or have a hard time making time for actual leisure time, and end up puttering around feeling weird for two hours instead? You guessed it, time-block the leisure time. Schedule intentional, forced leisure time, and treat it with the same respect you do every other block. Past you asked for some of your time, past you said yes. Plan around it.4 Thanks to my friend Kai Davis for this and the above idea — he’s mentioned it and similar things a couple of times on Make Money Online, which you should listen to, and elsewhere.

Have a hard time getting to bed at a reasonable hour? Time block sleep! (Full disclosure: I’ve never had much luck sticking to it scheduled sleep in the same way that I can most other things. The end of the day is hard that way. What I have found to work is blocking a specific wind-down activity directly before I intend to go to sleep.)

Never seem to take enough time off, because by the time you need a vacation everything is so busy that you won’t be able to walk away from your team for months? Block the weeks you want to take a vacation for the next twelve months right now, even if you don’t know what you intend to do with them yet. I have used this strategy to take a week off ten days before a major launch with no hard feelings or missed deadlines.

I think you get the gist, but just in case you need more ideas, this also works for finding time for regular date nights with a partner, time with your kids, time away from screens, time for reading (both for pleasure and professional development), watching less TV, watching more TV, sporting events, social time, goal setting, life planning, learning a new skill, and anything else you enjoy or want or need to do but never seem to have the time for.

This seems like way too much scheduling

It is a lot of scheduling, yes, but don’t think it’s too much. I think it’s an appropriate amount. Here’s why:

1. You don’t have to schedule everything in detail, just make the blocks, and only do the one thing during that block.

My standard evening block is just a chunk from 6:30–9:30PM that says “go home and stop working.” My morning writing time is not micromanaged; it’s just a big chunk too. I have a rough plan of what I want to get written in any given day, sure, but I don’t have a specific word counts or outputs or minute-by-minute breakdowns. The important part is that I have defended it from myself and others by blocking it off — my only option for that time is to write, which means I write.

Plus, if blocking the whole day scares you, just don’t block the whole day. Time blocking can be a highly effective tool even if you only use it to create one block of focused time and attention every day.

Long before I started blocking my whole day, I only had one daily block on my calendar: the time I needed to write. Making a writing block and and sticking to it without fail is how I have accomplished every writing project I’ve ever undertaken, including The Road Warrior book, my undergraduate capstone, and the blog you’re reading right now.

2. You can change the schedule at will, but only if you made it.

The whole point of this approach is to get the blocks of important stuff onto your calendar before everyone else divides up your day and your focus as they seem fit. It takes some work, but the alternative is having your life vigorously scheduled by people who don’t necessarily have your best interests in mind.

If that much rigor still spooks you, you can honestly just make a few big blocks, say from 9AM to 10:30AM, noon to 3PM, and 6:30PM to 10PM that say “busy” in your calendar and achieve much of the same time-and-focus-defense (although fewer of the organizational or anti-procrastination) benefits.

3. This approach may not be for you, and that’s fine.

You may in fact do better with less rigorous scheduling, and that’s A-OK. There are many paths up the productivity mountain.

I will make one note about it potentially not being for you, though: if you think it’s not for you because will “stifle your creativity,” you are likely wrong. I’ll let Newport bring this one home (emphasis mine).

Sometimes people ask if controlling time will stifle creativity. I understand this concern, but it’s fundamentally misguided. If you control your schedule: (1) you can ensure that you consistently dedicate time to the deep efforts that matter for creative pursuits; and (2) the stress relief that comes from this sense of organization allows you to go deeper in your creative blocks and produce more value.

If you’re still worried, read Mason Currey’s Daily Rituals: very few of the world-famous creatives he profiled adopted a “I’ll work when I feel inspired” attitude — they instead controlled their day so they could control their art.

Basic use

Think time blocking is for you? Awesome. Let’s get started.

Time blocking as a practice operates in four major steps: plan, block, act, and revise. What follows are the 101 version of these steps. I’ll get into a bunch of tips, FAQs and strategies for maximizing your time blocking at the end of the article.

Step one: plan

Before you actually schedule blocks of time, you have to know what you want to be doing during them.

Newport says he “consult[s his] task lists and calendars, as well as [his] weekly and quarterly planning notes. [His] goal is to make sure progress is being made on the right things at the right pace for the relevant deadlines.” Whatever system you use to do this, this is the goal.

I use a lightweight version of David Allen’s Getting Things Done (GTD) method combined with a higher-order categorization system based around projects and procedures; the only difference between the two is that projects are one-offs and procedures are regularly repeating projects, like keeping my inbox tidy and writing new articles for this blog.

Projects and procedures generally have milestones and deadlines. The tasks inside them do not, and look a lot like traditional GTD tasks. This lets me quickly figure out what will naturally go where in a day—long chunks of deep work first thing in the morning, collaboration after lunch, low-energy low-focus stuff in the late afternoon—while still moving my higher-order “project” goals forward.

Whatever you use, spend the time and effort to define your potential tasks in a concrete enough format that you can just pick them up and go without waiting on anyone or figuring anything out. (This will also let you more accurately estimate how long they will take.)

Step two: block

Put the things you have planned to do into specific blocks of time on your calendar. Most time blocking afficionados recommend blocking out your entire day at once, and I agree with this.

The only real question is when you should block out your day. Newport’s original version encourages a daily afternoon/evening practice that only blocks out the next day, but I prefer to do a draft weekly blocking on Friday or Sunday afternoon and then a quicker daily update based on how my week is progressing and changing.

If you need space for things that you know will take up time but you don’t know about in detail, that’s fine. You should still schedule them. I like to think of these less-structured blocks as “office hours.” If you need me urgently, I’m available — but only from 3:00 to 5:00 PM CST.

To that same point, in my daily planning, these office hours gets blocked for other tasks if there’s nothing scheduled in them by the evening before. This makes it so that when I wake up, I know what I’m doing all day — the value of which cannot be overstated.

It also means that to get on my calendar with less than 24 hours notice, you have to talk to me about it first, because I’ll have to move something to make the space. This is a good thing.

I’d also recommend blocking the time you get your best focused work done long in advance as a defensive action — I know my best time is basically from when I wake up to 11:00 AM, and I want that entire interrupted block whenever possible for writing and mission-critical design and coding work. My calendar reflects this; I currently have an activity that’s just scheduled as “Solo” from 8:00 AM to 11 AM every weekday this year.

I remove that block and replace it with more detailed blocks one to two weeks in advance. I can obviously can (and do) eat into my solo morning time for good reasons, but again, this practice makes it a conscious decision.

Step three: act

Your calendar will tell you what to do, and then you do it. This continues throughout the day until your day is over. Respect the blocks, and don’t do things that aren’t part of a block (like check email) during a block.

When it comes to transitioning to the next block, I like to set two reminders: ten minutes before it occurs, and when it starts. This gives me a chance to wrap up, do a little revision of the rest of the day’s blocks, and generally not be surprised by non-self-directed blocks like meetings and calls.

Step four: revise

There are two main times for revision: at the end of a block and at the end of the day. Revision at the end of a block means you estimated inaccurately; revision at the end of the day is future-facing, and reflects the fact that priorities change, stuff comes up, and projects take more or less time than you expect them to.

To be clear, neither of these things are a big deal. Your day will almost never go 100% how you expect, and that’s totally fine.

If you got done early, adjust your calendar to reflect that, and then either pull your next task forward, take a break, get a coffee, go for a walk, slot in a short “mosquitos” block and KO a few little things that have come up, whatever.

If you’re up against your next block, not done with the task, and still in the zone, just keep working and adjust to reflect reality later. Rather than push the entire day back, I prefer to pull whatever got bumped and move it to a holding area until my daily review — I just drag it down into the 10 PM–3 AM zone, where nothing’s ever actually scheduled.

If you can’t extend or think extra time later would be more valuable than extra time now (e.g.: if a task went over time because you’re just having a shitty, unfocused day, which happens to all of us), make an event in your holding area with the estimated amount of time left in the task and a little note in it to remind yourself of the discrepancy between how long you estimated and how much more (or less) time it’s likely to take.

Daily reviews are simple — look at any new tasks you captured throughout the day5 I highly recommend ubiquitous capture, even if you use nothing else from Allen’s GTD system. It’s much better than leaving it in all in your head where it will either be a distraction or forgotten. I like Leo Babauta’s notes on ubiquitous capture, which you can read here, and Merlin Mann’s, which you can read here and here., look at your holding area for any hangover blocks that need to get slotted in, and then re-block tomorrow and the rest of the week week accordingly. The “office hours” concept from above is helpful in ensuring there’s normally at least some time in the following day for urgent new things.

Additional assorted tips and strategies

You should now have plenty of information to go try time blocking for the first time, and I encourage you to. This is your last big call to action: go and try it! Even if it’s just making one block some time in the future for something you can’t seem to get around to.

But, if you are seriously thinking about using this technique, here are a few bonus random-access considerations:

Overestimate how long things will take

Generally speaking, everything will take longer than you expect for the first six months or more of using this approach. This is doubly true if you’ve never estimated your time before.

No one accounts for their time very well (you spend a lot more time “quickly” going to the bathroom and checking twitter than you think), and everyone assumes every time they sit down to their keyboard will be a perfect, undistracted working session, which almost never happens in practice.

For at least the first few weeks, I’d recommend blocking four times the amount of time you think it’ll for you to do something.6With thanks to Prof. Mark Pilkington who first gave me this rule of thumb. I scoffed at it at the time, and now I believe it to my core. This seems like an insane amount of buffer, but from my experience it’s actually about right. Email triage takes 15 minutes if you’re actually just doing email triage, but if you’re also doing all of the two-minute tasks that come up, drafting a couple of replies, stopping for the bathroom in the middle, and running into someone in the hall on the way back, email suddenly takes an hour, easy.

Plus, it’s a lot easier to find things to do with an extra half hour or hour at the end of the day than it is to find an extra four.

Don’t schedule everything back-to-back-to-back for the entire day

You are the master of your time, why be a cruel one? Leave yourself some gap time, some break time, some time to stretch and walk around and pee and get coffee, to switch tasks, to scroll through the headlines on your preferred news website, some undirected “sit and reflect” time.

The point of time blocking is to create a directed, focused flow throughout the day, not to feel like you’re running yourself ragged. Breaks are useful in this regard, and if you don’t schedule them, you’ll probably take them anyway. Then, if you’re like me, you’ll feel guilty about taking them because it’s not what you’re supposed to be doing. So just schedule the breaks. I like 5-15 minutes between blocks and a 50-minute block for lunch (even though it only takes me 30 or so to eat).

In Google calendar, Calendly, iCal and others, you can put these gaps into your default settings so that others have to respect them as well (or at least click an extra button not to).

If you work in an open office plan or a client-site team room, consider hiding in a conference room for some of your blocks.

This is an unfortunately necessary optics trick that keeps the “I’m booked solid!” line more effective for people who see you sit in the same place for calendar event after calendar event, and use that as a signal that you can be interrupted at will or scheduled over.

Reserve it for your deepest work, because it has the additional benefit of making you harder to find by other, kinder people who will nonetheless kindly interrupt you.

When it comes to interruptions, you are your own worst enemy.

Other people can be a distraction, but you are actually much more of a danger to your attention and focus than they are. When you’re in a block, turn off all notifications except calls7 Feel free to turn off calls too, but I leave them on because it’s the tradeoff I chose and communicated to my colleagues: I am not immediately responsive via Slack or email, but if it’s truly urgent, I will always pick up the phone.

, close your email, kill twitter, close all unrelated open tabs, and even kill slack if you can — especially for your biggest “deep work” blocks.

I use Freedom app for macOS and iOS to entirely remove the ability to visit those sites, because I have terrible self control. There are similar apps for PC and Android (FYI: that’s an affiliate link for Freedom, here’s a plain one if you prefer).

Don’t sweat it too much when things change, but give time grudgingly.

Blocks are ultimately just a best guess as to how your day will shake out, and they’re almost never 100% accurate. Stuff comes up, things take longer than you expect, an urgent crisis blows up your entire day. It’s not a big deal. Having a plan to work towards is much more important than precisely sticking to it.

BUT, as much as possible, make sure you are the person that chooses when and how things change. Last-minute regroups or meetings are always going to happen, but the whole trick of time blocking is that for sudden interruptions to be allowed, things have to move.

Make a show of it, even — show them your bright red calendar, then re-block right in front of them. Not only does this keep you honest to your priorities, it makes your client or colleague value (and feel valued for) the time they’re being given.

Related linguistic trick: I would recommend never telling anyone that you are “free,” at a given time ever. You “have time then” or “can make time” or “can move things around” or “can make that work.” Remind them subtly of the cost of your time and attention.

If you don’t have 10 minutes to block your time every day, take an hour

If you’re too busy to spend ten minutes planning for tomorrow, you are exactly the person who needs something like time blocking the most. Step away from all work for an hour and do a retroactive time blocking and a Pareto analysis on how you’ve spent your last few days. Is all of this work actually moving the needle? What can be cut? (nb: this will probably include meetings)

Then, keep yourself honest to your new to-do list by taking ten minutes to block it out. While you’re at it, make a block to do the same thing tomorrow.